Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

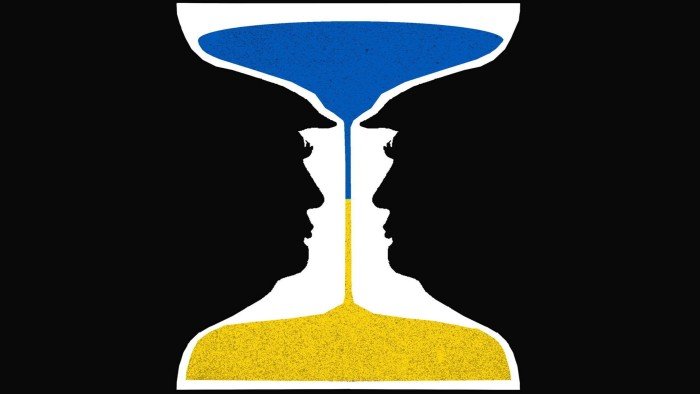

It is a millennia-old cliché of soldiering that you spend the majority of your time waiting around, interrupted by brief spasms of action. The same can be true of diplomacy. For a year now all parties to the war in Ukraine have been awaiting the results of the US election. Donald Trump’s commanding victory has ended that limbo — and supercharged thinking about an endgame in Ukraine.

Trump has long insisted that ending the war is a priority. For all the understandable questions about the path to a deal, America’s allies are assuming this is a promise he wants to keep. In Brussels there is a growing expectation there will be a ceasefire, if not some form of a settlement, next year. The challenge for Europe’s powers is how to guide the process to an acceptable end. America’s military pre-eminence gives Trump the dominant say in directing the process, but they do have leverage. They just have to use it.

Some will still nobly argue the only acceptable end involves Russian troops retreating to the borders as they were at the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Acquiescing in the formal change of frontiers is out of the question for Ukraine and most of its allies. But increasingly in Kyiv, Washington and across Europe there is a common view of the most likely outcome: a frozen conflict, with the issue of frontiers postponed indefinitely.

People close to Michael Waltz, the congressman who is Trump’s pick as national security adviser, and others among the president-elect’s foreign policy team, have talked of a version of the Korean Line of Control as a credible scenario, with agreed temporary borders. The critical questions are how to enforce such a deal — and of course how to bring Russian President Vladimir Putin to the table, given the fighting has tilted in his favour.

As for the policing of a deal, Trump’s confidants are adamant he would not deploy a single American soldier. The go-to solution of the 1990s, a force of UN blue helmets, is also out of the question given the impasse on the Security Council. This leaves Europe, whether via Nato, but without US forces, or a bespoke European force. It’s where European potential leverage comes into play.

Margus Tsahkna, Estonia’s foreign minister, broke cover this week and told the FT that Europe should be prepared to send forces to Ukraine to underpin a peace deal. In the language of Westminster politics, he was flying a kite. Interestingly, two days later the kite was still aloft, reflecting how European nations are starting to consider if and how they might agree.

Unlike in the cold war, when the fate of Europe was decided over their heads by Washington and Moscow, this time European diplomats believe they can have a say at the table given they can argue they will deploy troops only under specific conditions. Without such a guarantee, the risk of Putin seeking to test the mettle of a force by infringing the terms of the agreement would be too high for most heads of government to agree to dispatching troops.

There remains a nightmare scenario for Ukraine in which Trump pushes for a shabby deal on Putin’s terms. But Europe’s leaders are cautiously optimistic that Trump is listening to them and does not want to be the president who stood by as Russia over-ran Ukraine. “Trump wants to solve it but not at any cost,” says a senior European official. “It cannot be a capitulation of Ukraine,” or a debacle on the lines of Afghanistan four years ago.

And so the thinking is that Trump could sign off on security guarantees — albeit short of a commitment to Ukraine’s membership of Nato. One idea floated in his circle is a pledge to step back into the fray if Putin breaks the terms of a deal. In short, in theory at least, the Russian leader would not be allowed to undermine it, as he did the Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015, which supposedly drew a line under the fighting of the first stage of the war. The idea of stressing Ukraine’s long-term path to membership of the EU is also on the cards.

All this is predicated on the idea that Putin can be brought to heel. On the face of it, the potential of the war to escalate looks more worrying than ever. The Biden administration’s decision to let Ukraine use long-range missiles against targets in Russia, prompted Russia’s firing of an ICBM against Ukraine for the first time since its full-scale invasion in February 2022. But the west’s missile decision also underlines the catchphrase of the moment for Ukraine and its allies: “peace through strength”.

This slogan was first attributed to the second-century Roman Emperor Hadrian. In 21st-century Ukraine it signifies extreme pressure on Russia. Waltz told me in September that there are other ways of pressuring Moscow, including by unleashing cheap American oil on to the markets to weaken the oil-dependent Russian economy. Carrots will also matter, as well as the stick.

Much is still up in the air. Can China be leveraged into putting pressure on Moscow? What might happen to sanctions? Most of all, Russia may have no interest in a deal. But for now a logjam has been broken. Many of Trump’s appointments have met with eye-rolling from America’s allies, but not Waltz nor Marco Rubio, his pick for secretary of state. European officials concede that in his first term he did the right thing by forcing them to spend more on defence. Some now dare to ask if he might not be right in focusing minds on how best to end the war.

alec.russell@ft.com

Leave a Reply